St. Marys River Atlantic salmon stocked for fishing may be reproducing too

After nearly 30 years of stocking Atlantic salmon in the St. Marys River between lakes Superior and Huron, biologists have for the first time documented the species reproducing naturally there.

Though the paper announcing these wild-hatched salmon to the scientific world was just published in the Journal of Great Lakes Research in October, the fish were collected back in 2012 and none like them has been seen since, according to Stefan Tucker, a fisheries field worker with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources and lead author of the report documenting the fish.

“So was this one isolated event that where stars aligned and something happened, or did we just get lucky?” said Tucker, who found the fish more or less by accident while looking for young lake sturgeon as a Lake Superior State University student.

Fisheries managers had stocked hard-fighting Atlantic salmon across the Great Lakes on and off for more than a century without much success in establishing a fishery, let alone a naturally reproducing adult population. But the brains at LSSU’s Aquatic Research Laboratory in Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan, cracked the code in the late 1980s. The young, river-stocked fish weren’t heading out to the big lakes, but spending too much time in the streams where they were either eaten or met some other demise. The laboratory’s scientists found the solution: Keep the fish in the hatchery until they smolt.

With that knowledge in hand, the lab has annually stocked 20,000 to 40,000 Atlantic salmon in the St. Marys River since 1987, building a stable and popular recreational fishery.

“People come from all over the place to go and fish our Atlantics up in the St. Marys River,” Tucker said. “They’ll jump out of the water 6 feet. They’ll be out of the water more than they’re in the water when you’re fighting them.”

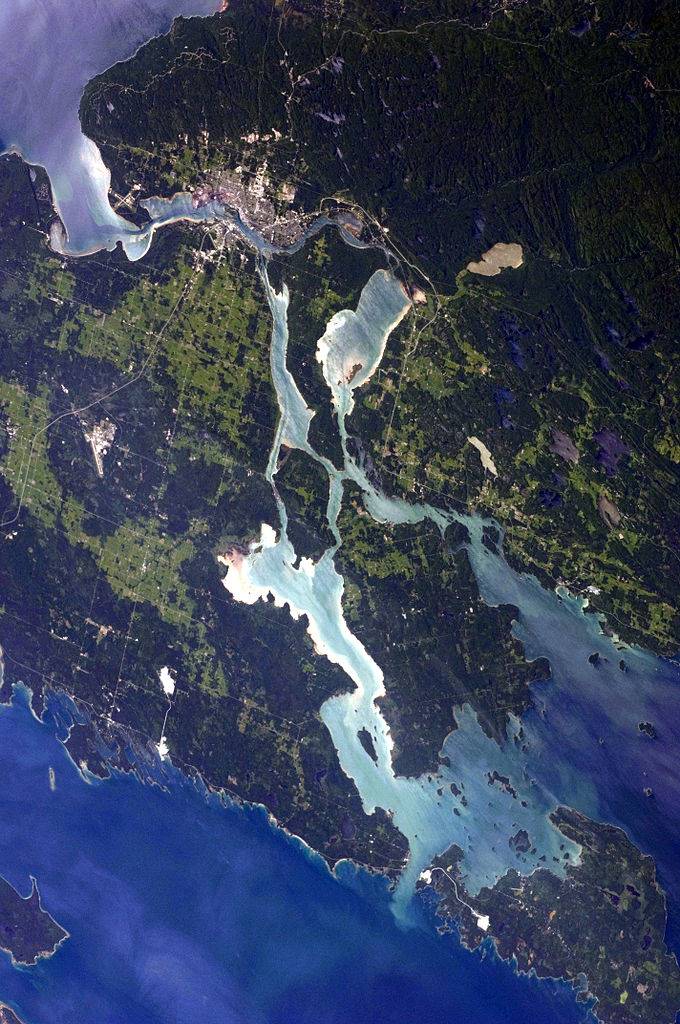

Atlantic salmon begin pushing up the southern end of the St Marys from Lake Huron in late May and June. (Credit: NASA Earth Observatory)

When the fish push out of Lake Huron and up the river in June, some anglers troll with spoons while others just float the river with a Gulp on a jig. By mid-July, the salmon’s diet shifts and anglers switch to something like a big perch rig with wire flies under a bobber. The fishery is especially popular with fly anglers who drift nymphs or swing streamers.

The stocking program’s goal was always to establish that recreational fishery and not to build a naturally reproducing population. It seemed unlikely, especially since the area where the fish are stocked, imprint and return is a hydroelectric plant that lacks proper spawning habitat.

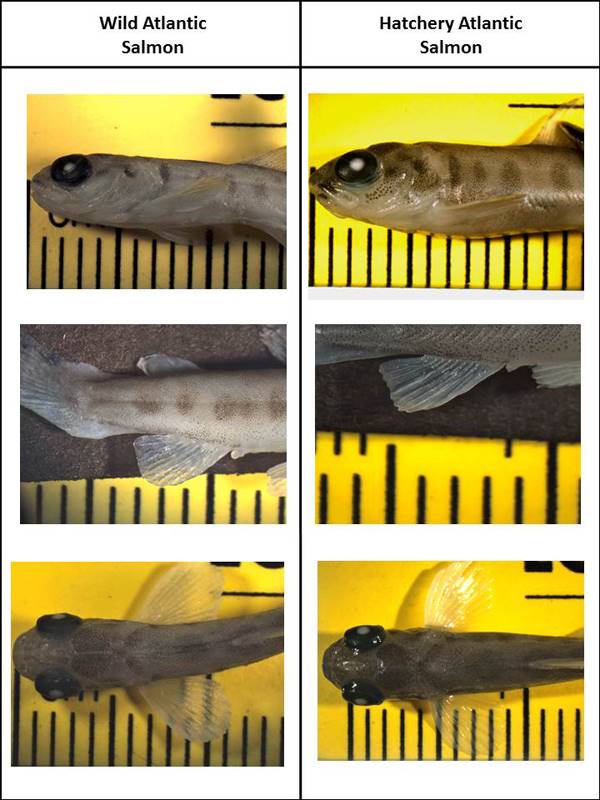

There have been reports of adult Atlantic salmon caught in the St. Marys without the clipped fins that mark them as hatchery fish, but they’ve been impossible to verify as wild fish. But the 25 little fry that Tucker caught are much younger than the stocked Atlantic salmon, leaving no other explanation except they were born in the river.

A comparison between the wild Atlantic salmon fry, left, and hatchery fish, right. (Credit: Stefan Tucker)

Tucker said the day he netted the wild young fish, he knew they had something salmon family in the sample, but didn’t make any assumptions.

“Once we got it back to the lab and we were looking through them, we were like, ‘Holy cow, these look like Atlantics,'” he said.

They did what they could to confirm it, and then sent a specimen to Gerald Smith at the University of Michigan, who is something of a guru of Great Lakes fish taxonomy. Smith agreed with their diagnosis.

Surveys since the 2012 finding haven’t turned up any more juvenile Atlantic salmon, Tucker said. But if more are hatching out there, there’s plenty more research to be done to figure out what that means.

“We know nothing about the behavior of these wild fish,” Tucker said. “It opens up a lot of questions.”

0 comments