When Females Outnumber Males, Mosquitofish Populations Hurt Ecosystems More

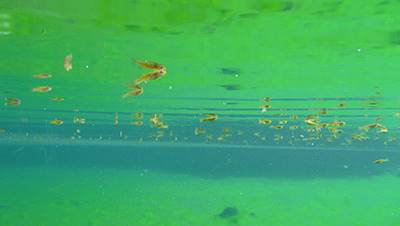

Western Mosquitofish, USFWS (Public Domain)

Western Mosquitofish, USFWS (Public Domain)Mosquitofish were largely introduced in areas to help control mosquito populations because they like to eat the insect’s larvae, hence their name. But over the years, scientists have found that the fish like to eat a lot more than just baby mosquitoes.

This tendency to chow down on whatever larvae are around has had broad ecological effects in some places. Good examples of this are Australia and New Zealand, where those who have contended with the fish’s appetite have started to call mosquitofish the “plague minnow” because of its impacts to ecosystems.

In an investigation looking to break down the dynamics of impacts that mosquitofish have on the systems they inhabit, researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz, set up a series of pools. These were used to figure out how the fish affected ecosystems depending on the ratios of males to females within their populations.

Results of the study are published under open-access license in the scientific journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B. They reveal that mosquitofish populations tilted heavily toward female dominance seem to have the most outsized effects on the ecological systems that they inhabit.

To begin, researchers filled the tanks at the university’s Long Marine Laboratory with sediment and plankton collected from nearby ponds. These steps let them basically establish miniature ecosystems within each pool.

Mosquitofish were added to the pools in five different sex ratios, while one pool was left completely empty of fish to serve as a control. Birds and other animals were kept out of the tanks (so they wouldn’t eat the fish), but amphibians and insects were allowed to lay eggs in them without restriction.

Going into the experiment, the researchers knew of mosquitofish’s reputation of having detrimental effects on native freshwater fauna. They also knew that female mosquitofish tend to be larger than their male counterparts. And so they had some expectations for what their investigation could uncover.

Mosquitofish have been introduced worldwide as a means of mosquito control. (Credit: Kevin Simon / University of California, Santa Cruz)

“When males and females of a species differ in traits like body size, they might use different resources or interact with the ecological community in different ways,” said Eric Palkovacs, an assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the university, in a statement. “As a result, the species can shape the ecosystem differently depending on the sex ratio of the population.”

Which is precisely what he and the study’s collaborators found. Since female mosquitofish prefer larger food items than males, and also eat more while surrounded by other females, the pools that had predominantly female mosquitofish registered some big impacts.

The females chowed down on the plankton, Daphnia, that scientists introduced, as well as larvae of insects and amphibians that laid eggs in the pools. The high feeding rates led to ripples in the food webs of each treatment pool, causing what researchers call trophic cascades.

“Daphnia are the principle grazers in freshwater ponds, keeping algal populations in check,” said Palkovacs, in the statement. “We found that female-dominated mosquitofish populations cause much more dramatic trophic cascades. When there are more males, the Daphnia population remains higher and algal abundance is lower.”

More females meant that water in the tanks was murkier when compared to the control pool or that in pools with more males than females. Scientists also tracked an increase in water temperature and pH in the female-heavy tanks.

“The magnitude of such effects indicates that sex ratio is important for mediating the ecological role of mosquitofish,” write researchers in the paper. “Because both sex ratio variation and sexual dimorphism are common features of natural populations, our findings should encourage broader consideration of the ecological significance of sex ratio variation in nature, including the relative contributions of various sexually dimorphic traits to these effects.”

0 comments