Wisconsin Muskie Spawning Habitat Study Addresses Decline

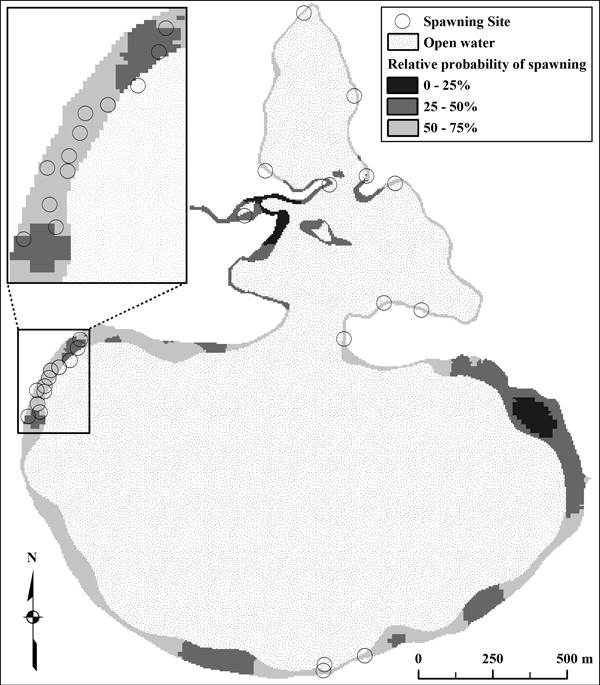

The model produces maps of potential muskie spawning habitat like this one for Harris Lake in Wisconsin. (Credit: Joel Nohner)

The model produces maps of potential muskie spawning habitat like this one for Harris Lake in Wisconsin. (Credit: Joel Nohner)Back in the spring seasons of 2007 and 2008, coordinated crews of muskie enthusiasts took to 28 northern Wisconsin lakes in the cover of darkness, gliding over the black waters to shine spotlights on muskie spawning habitats looking for lurking fish. Though it was outside of muskie season, the work was all above board: These volunteers from the Muskie Clubs Alliance of Wisconsin were working with state and university biologists to address the decline of the region’s premier sportfish.

“You have a lot of die-hard muskie anglers that are getting cabin fever, wanting to get out on the water and wanting to see fish,” said Joel Nohner, a doctoral student in Michigan State University’s Department of Fisheries and Wildlife. “Many of them just had a conservation ethic and wanted to do what they could to help the resource.”

Competitive Research

Nohner, a master’s student at the University of Michigan at the time, was among the researchers from the school and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources coordinating the muskie-spotting crews. He said the thrill of seeing 40- and 50 inch muskie in such shallow water never wore off, even after marking dozens of fish. The volunteers were into it as well.

“There was definitely competition going on amongst the crews to see who saw the most fish and the biggest fish,” he said. “Some boats wouldn’t have seen a fish all night, and another boat would have seen 45.”

But it wasn’t all about ogling fish after a long winter. They were marking the locations of the fish they found, building a record of the areas of each lake that muskies were using as spawning habitat. The species’ natural reproduction is declining throughout its native range, and protection and restoration for spawning grounds could help. Through these surveys and some computer modeling, managers are identifying high-priority spots for conservation work in lakes where the species naturally reproduces.

The surveys gave muskie enthusiasts a chance to watch fish during the closed season. (Credit: Bob Haase)

Comparing Past Muskie Spawning Habitat Research

Though past research and observations have produced some conventional wisdom about where muskies spawn, the results of this study shows that the species doesn’t always seek out the stereotypical habitat of weedy, mucky back bays with woody debris. After combining the muskie location record with maps of lake bathymetry and vegetation, they found quite a few muskies that appeared to be spawning over sand. And while spawning muskies appeared to gravitate toward areas with submerged vegetation in clean and clear lakes, they avoided those plants in eutrophic lakes.

“It’s not as straightforward as we initially thought,” said Nohner, also affiliated with the Center for Systems Integration and Sustainability at Michigan State.

Muskies showed the strongest selection for moderately sloping shorelines and small areas of flats within bays — but not the mucky back bays. They were in “intermediate” bays with more access to the main lake that likely freshened up the water.

Muskies also selected not to spawn near sites of shoreline development. Previous research had shown that lakes with more shoreline development tended to have lower rates of production producing young muskies, but this is the first study to specifically show that the species avoids those areas when it comes time to spawn.

Cautions Surrounding Future Development

“We really need to think hard about how we’re doing shoreline development so that we can apply best management practices and minimize our impacts on muskie spawning,” Nohner said. “I’ll leave it for the managers and the public to decide the best way to do that, but we know that developed shorelines are impacting muskies.”

The researchers also used the data to create a computer model that predicts muskie spawning habitat in lakes. By plugging in bathymetry and other data on the lakes, the model produces an estimation of sites muskie are likely to pick for spawning. That could prove useful for habitat restoration or conservation efforts in the hundreds of other lakes in Wisconsin where muskie naturally reproduce but haven’t been surveyed like those 28 lakes in 2007 and 2008.

0 comments